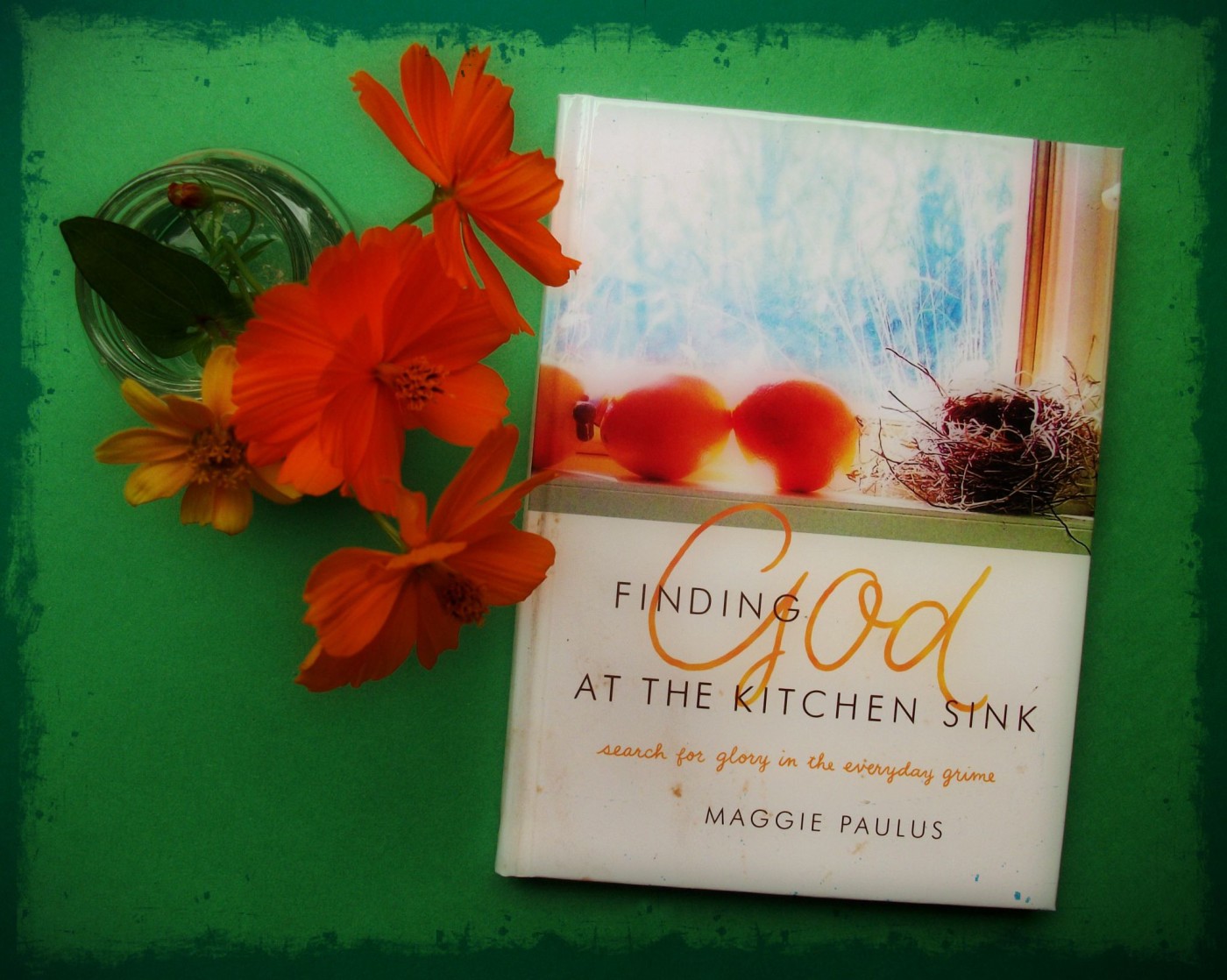

Over the next week or so, I plan to post a few synopsis’ of my book.

The first one comes from my friend Jeremy Allen, whom I have a deep respect for.

Jeremy is insatiably curious. He is a researcher, professional photographer, map lover and sometimes poet. After 32 years in the Christian faith, a tour in the Army irrevocably shook his faith. As an agnostic he now pursues graduate studies in philosophy and social theory.

You can find out more about him here, at Eighteen Chains.

Maggie is a spirit full of the world’s wonders. The dirt in her sink, the snowflakes on her kids’ faces, and the farthest corners of the universe do not escape her delight. Her heart bursts onto these pages in word-images bright as the sun. But Maggie knows darkness, too. She experiences tragic loss and desperate longing. She aches deeply for something, and someone, to make it right. And she finds.

In this book of episodes, Maggie opens many small windows. Into her painful past: “The way my momma was gentle and easy-going when she was sober. I always wanted to sleep next to her.” Into her joyful wrestling matches with laundry: “That makes cleaning not so hard. It actually even transforms it into a way to worship.” And her thrills and spills of marriage and momma-hood: “God would be my strength as I learned to craft love, the stuff that lasts forever, a thousand times a day in a hundred different ways,” and “I certainly never knew how much I’d cry. All these happy tears.” And especially into her doubts in and devotion to the Christian God who makes it all possible for her: “So, one night I fought it out with my Maker. I asked Him hard questions and begged of Him answers,” then “somewhere in those wee hours, I relinquish control and abandon myself to the One who never sleeps.”

These episodes express Maggie’s everyday encounters with a fistful of oppositions: abandonment and belonging, brokenness and wholeness, fear and hope, evil and good, and doing and being. The careful reader is wise not to judge each episode alone – any one may raise more questions than answers – but will follow Maggie on an honest journey of finding her way in a world where “everything else totters and fluctuates, but not Him.”

In the flux there are contradictions that Maggie could wrestle with more vigorously. For example, the skeptic, and I am one, will wonder why the God who “turns toward you and seeks to bless you” could be the same God who allows bad people to “do wrong things to little people when no one else is looking.” Quoting scripture and praying doesn’t seem enough to resolve the contradiction. But Maggie embraces faith with a bear hug that is big enough to include contradictions and the kitchen sink. And she loves on. Something both believers and skeptics can embrace.